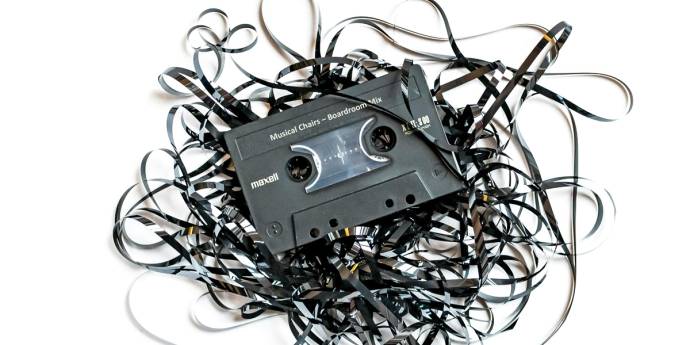

When the music stops

We all aim to add value to our boards, but the chair is the lynchpin, providing leadership, developing the governance culture, ensuring there are strong communication flows between the board and management, and creating the vital link with the chief executive. The chair’s behaviour and performance – good or bad – has a disproportionate impact on a board’s effectiveness.

The fruits of successful leadership include stronger decision-making, employee engagement, increased productivity, positive organisational culture and enhanced financial performance. But as the saying goes, the fish rots from the head. Think Enron, Lehman Brothers, Boeing, BBC, Crown Resorts (Australia) and more.

While we can all have style and personality differences, poor leadership impacts on the ability of boards to work together and achieve consensus decision-making. A good leader is someone who can build trust and confidence, engage and motivate people, and influence others to work together towards a shared goal. To achieve this requires emotional intelligence, qualities such as empathy, integrity, humility and self-awareness, ironically generally referred to as soft skills.

We have all encountered bad bosses that have risen to the top despite having the wrong skills for a leadership role. We also recognise leadership is dynamic, and the skills we expect and want from leaders have changed and expanded over time, as also recognised in some legal judgments.

The autocratic days of command and control are thankfully (hopefully) well behind us, replaced with recognition of the value of soft skills and the need for servant leadership, where people are put first.

Wakatū Incorporation director Miriana Stephens MInstD shared a saying she was taught when she was younger that sums up servant leadership perfectly: “If service is beneath you, then leadership is beyond you.”

Without necessarily any reduction in hard skills, such as industry knowledge, technical skills and financial management, what brings these all together to make a good leader are people-centric skills, such as agility, adaptability, authenticity, innovation, creativity and relationship-building.

“Like any significant corporate decision, you need to carefully consider the impacts, including brand and stakeholder implications, as well as business continuity.”

The CEO and chair have similar roles, albeit at different levels. And in the same way that you need to ensure the CEO is the right person for the role and hold them to account, the same applies to the chair (and board).

While legally, all directors are equal, the chair is frequently referred to as ‘first among equals’, recognising their role in driving board effectiveness and best-practice governance.

Ultimately, the chair’s role becomes untenable at the point they no longer enjoy the confidence of the board. The process of removing the chair will depend on the entity, legal structure, bylaws and mechanisms available. But even if these elements are stacked in your favour, it is a major event with repercussions inside and outside the boardroom, so it should not be taken lightly.

Like any significant corporate decision, you need to carefully consider the impacts, including brand and stakeholder implications, as well as business continuity. Focus on the organisation, not the individual. Ultimately, this is about what’s best for the company. The chair’s resignation or removal may stop problems from becoming worse and provide investors and stakeholders with the confidence they need.

Ideally, changing the chair should be done with sufficient lead time to enable a robust succession planning process to be undertaken. Where this is not possible, a robust process, even if severely truncated, still needs to take place, and legal advice may need to be sought and/ or an independent third party engaged, especially if the chair is not prepared to go quietly.

There should be policies and procedures at hand to support the process, including code of conduct, board charter and performance evaluations. While board evaluations are becoming more commonplace, a separate evaluation of the chair’s performance is an important element that shouldn’t be regarded as an add-on.

An independent evaluation helps to remove any perceptions of bias, is more likely to unearth real concerns, and can support how the report is received and what is done with the information, particularly if a facilitated feedback session may be required. Seeking broader feedback from your CEO and executive team in relation to the chair’s performance can also be beneficial.

Where the chair is appointed by shareholders or members, having annual performance reviews, including broader feedback on the chair’s performance as well as transparency about meeting attendance, can help inform their re- appointment considerations.

“Regardless of how difficult it might be, direct and honest communication is essential. Try to address issues up front, either one-on-one, through the deputy chair, as part of performance feedback, or as a board.”

As Mark Verbiest CFInstD told Boardroom in the summer 23-24 edition, “When directors don’t seek feedback it often raises questions in terms of how self-aware they might be, where they genuinely think they have contributed and how effective they believe they might be.”

However, you shouldn’t leave concerns until the point where you feel that removing a chair is the only option.

Regardless of how difficult it might be, direct and honest communication is essential. Try to address issues up front, either one-on-one, through the deputy chair, as part of performance feedback, or as a board.

If the behaviour is new, listen and give them the opportunity to reflect on their behaviour, and seek to identify stressors or challenges they may be facing so they can be supported in their role, such as through training, mediation or a leave of absence.

If their behaviour or underperformance is an ongoing and/or serious concern, engage the rest of the board and ensure you have gathered concrete evidence and can identify specific issues that need to be addressed. A consensus about how to deal with the matter will be important to reduce the potential of further fracturing of the board and support the legitimacy of your claims.

Nonetheless, navigating the process can be hard. The situation needs to be handled with care, sensitivity, professionalism and confidentiality. Ensure transparency and that you are adhering to proper processes, such as convening and minuting a board meeting to decide on the best course of action. Do not make hasty judgements, but similarly, don’t leave things until they are rotting.

Judene Edgar CMInstD is a Senior Governance Advisor in the Institute of Directors’ Governance Leadership Centre. She is an experienced director and currently is a trustee with Network Tasman Trust and Rātā Foundation, and Chair of the Nelson Historic Theatre Trust.

Judene Edgar CMInstD is a Senior Governance Advisor in the Institute of Directors’ Governance Leadership Centre. She is an experienced director and currently is a trustee with Network Tasman Trust and Rātā Foundation, and Chair of the Nelson Historic Theatre Trust.