Quick takes

NZX Director Independence Review update: implications for directors

Changes announced will enhance robustness of governance practices for New Zealand-listed issuers.

How can those with governance roles influence desired behaviours from behind closed doors?

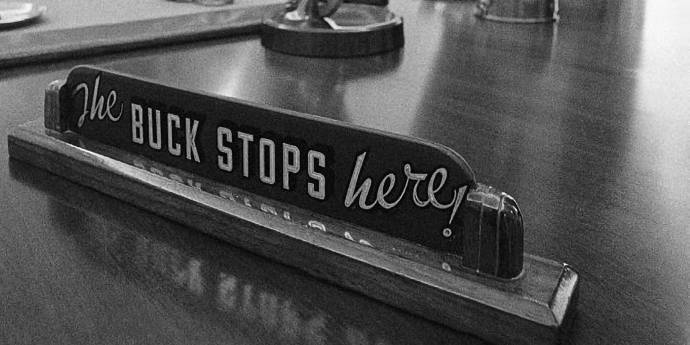

US President Harry S Truman kept a wooden sign on his desk saying: “The buck stops here”. The sign stood as a reminder that whoever sat behind that desk needed to make decisions and accept responsibility for the outcomes.

However, in governance documents, statements that remind us of who is accountable are often buried deep.

Roles and responsibilities of those who sit at a board or committee table can become warped over time. A post-mortem of the global financial crisis clearly pointed the finger at those sitting around such tables.

Board members who bathed in the glory of privilege prior to the collapse of the financial markets may have benefited from the “buck stops here” mentality, sitting boldly on a block of wood, watching over their decisions. It could have been one of the cheapest, yet most effective, hard controls ever implemented.

This ethos is applicable across the wealth management sector. While privately-owned firms are not obliged to apply the NZX Corporate Governance Code requirements that their public counterparts are expected to comply with, the influence of good governance, and proactive accountability, should not be discounted.

Arguably, both public and private entities, especially those involved with offering products into which their customers invest for their futures, should aspire to not only comply with those higher expectations but to view the rules applied to the publicly-listed companies as a benchmark to build upon.

History has shown that good risk governance is the difference between prosperity and failure. However, those in governance positions have only the sum of their personal experience, knowledge and capability to guide them - particularly when decision making lies outside their area of expertise. This raises the question – are those in risk governance positions knowingly accepting of this level of personal accountability? Or are they looking at their fellow members to be accountable on their behalf? After all, isn’t that why others have also been elected to the table?

We know that risk culture drives the performance of an organisation. By influencing and encouraging desired behaviours, we trust our people to make the “right” decisions for the organisation. The synergy of these decisions - whether micro or macro, frontline or board level -is shared with everyone as performance indicators.

The key to unlocking performance is understanding the desired behaviours you want to focus on.

One of the most influential behaviours that connects the board to their leaders is role modelling; the values of an organisation require constant reinforcing if they are to live beyond a few placards on the wall. While governance meetings may happen under a veil of secrecy, members should not discount the many eyes analysing them. These governance meetings either support the notion that organisational values are being genuinely lived and breathed, or not.

Within our organisations, we look to those around us for indications of norming; the way we do things around here. If we can’t directly see our formal role model or leader, we will seek out people in our closer vicinity and adopt them as our role models. It is essential that an organisation’s leadership is visible, and demonstrating the right values.

The same applies to those who are ultimately accountable, and this begs the question - how can those with governance roles influence desired behaviours from behind closed doors?

Good governance relies on groups of people making decisions. While we provide diverse minds to enable the best environment for decision making, the outputs will be heavily influenced by the inputs.

A trend is emerging with the rise in the quantity, accuracy and manipulability of data. Where governance groups used to rely on insight and gut feel from the report authors, this has given way to metrics, graphs and technical data. Not only is the content more complex - but the sheer volume of content seems to be expanding.

This provides a real human challenge as board members need to be able to absorb the content to inform their decision making. Unless this upload can be achieved (and sometimes only on a small screen at 35,000 feet) it may be difficult for the audience to critically interrogate and challenge the reports. Further to this is the over refining of information. As more focus is being placed on delivery objectives such as on time and on budget, the sacrifices made to provide this green light reporting can be overlooked. Reports can be over-edited, but is this for the benefit of the author or the audience? Or worse still, key risk indicators are buried under swathes of technical information and jargon in a bid to offload someone’s responsibility.

Often within risk governance documents, responsibilities assigned to members may include such phrases as “determine if effective” or “responsible for the effectiveness”. These indicate a level of assessment is required.

For example, if a responsibility indicates a member must “determine the effectiveness of the risk management framework” this goes much further than seeing evidence that such documents exist. It goes further than discussing the quarterly heat-map or relitigating the assessment of a “very high” risk so it becomes a more palatable “medium” risk.

To determine the effectiveness, it would be necessary to conduct a post-mortem analysis on a risk that was realised and became an “issue”. Was the risk identified and on the right register? Were the controls effective as reported? Were there controls in place to limit the impact? How

did we respond? What are the new risks? Have we refined our process?

People with governance roles will continue to be held accountable for their decisions - individually and as a collective. In order to fully discharge this responsibility, they need to look to the suite of governance documents for guidance. These instruments should clearly outline where the accountability starts, and stops.

How those with governance roles go about fulfilling this duty will always be under scrutiny. Shaping the board reporting so content is directly aligned to governance responsibilities will go a long way towards optimal decision making.

By being more deliberate and visible in their actions, governance members can be accountable by positively influencing the behaviours of their organisation. And ultimately, play a part in the many decisions made every day that contribute to performance.

The buck stops here. Nowhere else.

This article was first published in the 2019 KPMG Wealth and Funds Management Publication: An evolving landscape. You can read the full publication at kpmg.com

Author: Rachel Pettigrew, Risk Advisory Associate Director at KPMG

This article is featured in Boardroon issue December January 2020