Courageous boardroom conversations

Moving on or ‘getting rid’ of that non-performing or problematic board member isn’t necessarily easy, even if you’re the board chair.

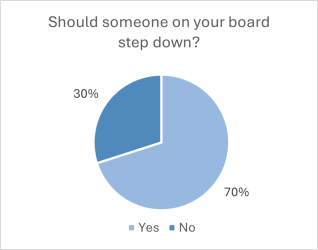

In our pulse survey in June, 70 per cent of directors said there was someone on their board that should step down. These results mimic those from a 2023 survey by PwC in the United States of more than 600 public companies, where 62 per cent of CEOs said one or more directors on their boards should be replaced.

In our pulse survey in June, 70 per cent of directors said there was someone on their board that should step down. These results mimic those from a 2023 survey by PwC in the United States of more than 600 public companies, where 62 per cent of CEOs said one or more directors on their boards should be replaced.

There are many different reasons behind this including a desire to increase diversity, addressing under or non-performance or problematic behaviour, changing strategic focus, or simply to refresh the board. While addressing this is not always the easiest conversation to have, avoiding it can lead to even bigger issues.

Problematic board members can:

- Undermine the authority of the board

- Negatively impact organisational reputation

- Delay or derail critical decisions

- Disenfranchise or disengage other board members

- Negatively impact on boardroom culture

The concept of the right person at the right time for the right role is still pertinent. However, this isn’t static (for example, company strategies change over time), and how you define the ‘right person’ for your board today, won’t necessarily be true in the future.

Having ongoing conversations about board skills, diversity and abilities is easier than dealing with things once they get to breaking point. This is similar to issues with conflict on a board that need to be dealt with early on.

Similarly, there is no ‘right board’. In order to meet the long-term strategic challenges and opportunities of your organisation, your board composition needs to evolve and can’t rely on this happening organically because you could lose vital experience or intellectual property at critical times or, conversely, have skills or expertise gaps. And even the best board can become stale over time. From the pulse survey, only 61 per cent of the directors who responded said their boards used a skills matrix. This aligns with the 2023 Director Sentiment Survey with 64 per cent of directors reporting that their board regularly discusses board composition/renewal and the skills/experience needed now and for the future.

From the pulse survey, only 61 per cent of the directors who responded said their boards used a skills matrix. This aligns with the 2023 Director Sentiment Survey with 64 per cent of directors reporting that their board regularly discusses board composition/renewal and the skills/experience needed now and for the future.

Having and updating a board skills matrix on an annual basis is a good first step. Reviewing the skills matrix is an opportunity to look beyond the here and now, and consider the skills mix needed to achieve the strategic plan (gap analysis); and the training or upskilling that might support the board to do this (performance improvement). Boards and directors should approach this from the perspective of the best interests of the company or organisation.

The operating environment for boards is increasingly challenging, putting pressure on them to have competency beyond the more traditional areas which now include AI, technology, cybersecurity and climate change. Similarly, skills such as health and safety, human resources, supply chain expertise, nature, and brand/communications can be critical around a board table.

Board composition goes beyond the skills, qualifications and experience of directors to tenure, size, structure and number of committees and meetings. It can be influenced by entity type, legal parameters, industry and maturity. Getting the board structure right also needs to evolve to reflect the current risks and opportunities the board is grappling with. For example, many boards have established sustainability committees to support their transition to a zero-carbon economy or technology committees to evaluate the impacts of AI and cyber.

Recognition of the increasingly complex environment was reflected in the significant drop in 2023 Director Sentiment Survey respondents who considered their board had the right capabilities to deal with increasing business risk and complexity (47.4 per cent, well down from 59 per cent in 2022). Despite this, only 50.2 per cent of boards stated they regularly undertook formal board evaluations. The pulse survey results reflected similar trends with only 45 per cent having undertaken an evaluation within the last two years and 39 per cent having never undertaken a performance review.

Recognition of the increasingly complex environment was reflected in the significant drop in 2023 Director Sentiment Survey respondents who considered their board had the right capabilities to deal with increasing business risk and complexity (47.4 per cent, well down from 59 per cent in 2022). Despite this, only 50.2 per cent of boards stated they regularly undertook formal board evaluations. The pulse survey results reflected similar trends with only 45 per cent having undertaken an evaluation within the last two years and 39 per cent having never undertaken a performance review.

Consideration of the skills around the table and regular board evaluations may be more critical than ever. Board evaluations provide valuable opportunities to not only improve board performance, but to pinpoint areas for enhancement and change including structure, culture, and boardroom dynamics, and identifying skills gaps, director development, and addressing underperforming members. Having an independent review can provide directors with the safety and security that a whistleblowing policy provides for staff, especially when needing to start the courageous conversations about problematic board members, and even moreso if it is the chair.

In accordance with the IoD’s 2022 Directors’ Fees Report, the average length of a directorship in New Zealand is six years, but some definitely stay longer. In the pulse survey, 43 per cent of boards had a term limit of up to six years, but 41 per cent had no term limit at all.

In accordance with the IoD’s 2022 Directors’ Fees Report, the average length of a directorship in New Zealand is six years, but some definitely stay longer. In the pulse survey, 43 per cent of boards had a term limit of up to six years, but 41 per cent had no term limit at all.

While there are valid arguments for longevity, retaining knowledge and stable leadership, there are inherent risks that come with a lack of turnover or an absence of succession planning. One of the key lessons from the collapse of the Enron board in 2001 is attributed to the perils of groupthink, which can be toxic and inhibit innovation, good decision making and lack of analysis. Consequently, there has been an increasing focus on the benefits of board diversity as one of the keys to overcoming groupthink and facilitating wider debate.

With less than half of respondents to the pulse survey rating their boards as excellent (13 per cent) or good (31 per cent), it’s clearly time for some courageous conversations.

Considerations for directors:

- Have robust recruitment and assessment practices in place including consideration of increased diversity

- Set clear roles and expectations for board members and an effective induction process

- Have tenure limits in place or a process that regularly reviews individual director performance and contributions

- Undertake regular board evaluations as well as informal feedback mechanisms to provide opportunities to raise or address issues before they become problematic

- Have a board skills matrix and regularly review to identify skills gaps and development opportunities

- Have policies and procedures in place to address conflicts of interests that also assess each director’s independence from the company/organisation

- Have an agreed code of conduct and attendance expectations

- Address issues early on (and seek mediation or facilitation if needed)

- Actively encourage and support the change you need to create a better working relationship

For further information about the benefits of board evaluations, find out more about our services here.