Signals ignored: the UK Post Office scandal and the cost of governance silence

A recent webinar on the UK Post Office scandal highlights what boards must do to challenge culture, data and direction.

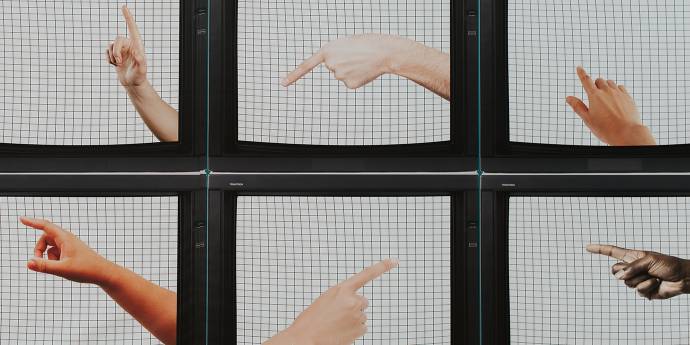

Board chairs share their practices that can build your board culture.

A recent study of New Zealand boards revealed substantial differences in relation to their diversity of thought. They varied widely not just in their potential for diverse thinking but also in the extent to which their culture supports the realisation of their diversity of thought.

Following on from those findings, the chairs from four boards with high-performing cultures in that study were interviewed to learn about the practices boards can use to develop a culture that enables diversity of thought.

As these boards demonstrated their positive cultural performance through the DOT Scorecard® – an insider’s 360-style evaluation – the selection of interviewees has an objective basis, in contrast to the more typical selection method of relying on a board’s profile and external perception of its performance.

For this reason, these interviews present a unique opportunity to gain insights into boards where diversity of thought is measurably at work. The interviews have been collated into five articles:

“I think it's all about psychological safety and that everything you do when you do bring in somebody's opinion contributes to their psychological safety.”

Ngaio is chair KiwiNet, director Reefton Distilling Company, co-founder Nuance Connected Capital, Portfolio and Investment Manager Lewis Holdings. She was previously director Everedge Global, and director Precision Engineering.

“The management team should feel that it’s safe to present different perspectives to those expressed by the board and to share that they disagree with board members. Everyone should then be curious about why those different perspectives exist.”

Abby is chair Z Energy, independent director Freightways, and independent director Sandford. She has previously been a director TVNZ, director Museum of NZ Te Papa Tongarewa, director Livestock Improvement Corporation, director Local Government Funding Agency, director BNZ Life Insurance, director Diligent Corporation, and director Transpower.

“To develop trust and respect, it’s really important to get to know the person outside of the boardroom.”

Janine is chair REANNZ, and executive director and principal of The Boardroom Practice. Previously she was chair AsureQuality, director Steel and Tube, director Kensington Swann, director The Warehouse Group, deputy chair Kordia, BNZ, deputy chair Airways, executive director Arnott’s NZ.

“You've got to observe what's going on around the table and avoid the dominance – you’ve got to call those out who are talking over others or are repeating themselves. You need to invite people to speak up where they have not been able to do so.”

Frazer is currently South Island vice president NZ Law Society, council member, chair of Appeals Board, chair of Health & Safety and Ethics Compliance Committee University of Otago, and a partner at Anderson Lloyd. He was previously chair of Anderson Lloyd Partnership, and served as chair of Presbyterian Support Otago.

Psychological safety is the shared belief that a group is safe for interpersonal risk-taking. It is about being able to be and show one’s self without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status or career. Psychologically safe board and team members feel both accepted and respected.

Based on her research and experience, Janine characterises psychologically safe boards as those where members respect and trust each other. Structuring in time for people to get to know each other outside of the boardroom is critical to developing relationships of this nature.

“They don’t just know each other from their board time, they actually start to know each other as people. I've seen that work extraordinary effectively.”

Ngaio sees psychological safety as going beyond allowing someone to be themselves; for her, in a boardroom context it’s specifically about allowing an individual to disagree with the rest of the board. She believes that everything you do as chair, including actively bringing in somebody’s opinion, should contribute to their psychological safety.

“It's also about ensuring that there is never a witch hunt – that if something goes wrong, there isn’t an allocation of blame back to the suggester.”

To Frazer, an important part of the chair’s role in building a psychologically safe board is preventing someone from dominating.

“You've got to observe what's going on around the table and avoid the dominance – intervene and stop people talking over each other – and then when things get a little bit heated, you’ve got to call those out who are talking over others or are repeating themselves. You need to invite people to speak up where they have not been able to do so. Ideally you shouldn't have to do it but it does happen, and I think it's managing a situation to make sure that no one overbears anyone else.“

While Janine does not recall many instances of poor behaviour on her boards, she acknowledges that establishing and maintaining trust and respect does require more work where board members are diverse.

When behaviour is detrimental to psychological safety – such as over-talking – Janine believes it is best tackled proactively. Interestingly, the person responsible for such behaviour can be completely unaware of its impact.

“I have had times when a female board member has come to me suggesting that one of the males was perhaps over-speaking, not quite being a bully but behaving in a way that was of concern. You raise it with them and they have no idea by the way, so you just have to manage that.”

As Abby explains, boards that demonstrate high levels of psychological safety feel free to share their concerns. They do this in a way that stimulates the curiosity of others and opens opportunities for others to build on to thinking, as opposed to being defensive or reflexively challenging in response.

Where a board has psychological safety, Abby says, it allows for really robust debate about different perspectives and then makes it possible to move on to the next issue, where board members may form entirely different combinations of views. Plus, you’re confident that everyone’s still really comfortable with each of the relationships around the board table.

Ngaio further emphasises psychological safety is a safety net for the individual rather than collectively for the board as a whole. In her view, a critical education piece is to consider how board members feel when the board does not follow their idea but they did contribute to the decision-making process and a better decision.

“If you have someone who's really against the direction of the group as a whole, I'll say, ‘Okay, so you clearly disagree with the direction of travel here and I know that when we leave the room, we all have to agree, so what can you live with?’ and then we'll try and find some common ground, which means that you haven't won but you haven't lost either.”

Ngaio encourages converting an absolute “win/lose” mentality to a more nuanced view from board members, where they think: “I contributed, I helped, and I got there and I don't need to wed myself too closely to my idea as being absolute, as long as parts of my idea or some of my considerations have been heard.”

Ngaio has also observed that new board members can be put under some pressure when the existing board is keen to make the most of their “fresh set of eyes”. She sees the solution as giving people fair warning and good notice to prepare to make their contribution:

“We're currently discussing this. You're quite new to this board, and when we get to the end I'm going to ask you what you think, and if you have no extra thoughts, that's fine, but if you do have a different perspective, we would love to hear it.”

Ngaio reports that in most cases people do then share their thinking; in fact, they often see something others hadn’t thought of. Going through this process once or twice gives people the encouragement they need to know that their ideas are wanted and valid.

“Even if the idea that comes through is outside the brief, or goes right against everything already proposed, it's a matter of acknowledging ‘that's a great framework for reviewing what we do, and making sure that it does fit with what we're supposed to be doing so thanks for bringing that framework in’. But that’s the psychological safety net: knowing that you are necessary as part of our overall decision-making, not that your individual ideas will necessarily be acted on.”

Abby shares how psychological safety should also be a priority consideration for the board’s interaction with management: “The management team is a really important part of wider board culture. They've got to feel that they're part of that journey and there's psychological safety for them as well as for the board.”

Abby acknowledges that the work of the broader group of management and governance can be fraught at times. She explains that you need to keep watch on the relationship because you want to make sure that the management team feel challenged and held to account for their part but equally that all of the people around the table have mutual respect.

“The management team should feel that it’s safe to present different perspectives to those expressed by the board and to share that they disagree with board members. Everyone should then be curious about why those different perspectives exist.”

Download Realising your board's diversity of thought series as a PDF.

Lloyd Mander CMInstD leads DOT Scorecard, a consultancy that works with boards, executive teams and other teams to understand potential for wide-ranging diversity of thought and develop the decision-making culture that is required to realise diverse thinking.

He represents the Canterbury Branch on the IoD’s National Council and has held governance roles associated with the health, housing, transport, and entrepreneurship. Lloyd was previously a co-founder and the Managing Director of a regional healthcare provider.